We're coming into the Panama Canal.....it almost looks like a Naval Battle....there are ships everywhere! Apparently the largest ships that come through are 900 feet in length. Also, there is a "lock" system, which raises the ship about 30 feet, and allows it to be carried through the canal (basically, over the land).

Hope you've all enjoyed our updates....ranging from the scientific to the whimsical. It's been a great experience--we've learned a lot, about marine geology, bathymetry and even bird watching. We survived the tropical depression (which eventually became Hurricane Greg) and even sighted the occasional whale.

Perhaps our next adventure will be from the deep, in a submersible

....will keep you posted.

Scientific Crew

Reporting from the R/V Melville

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Day 11: Ridges and Radar

The images above are wave cut platforms, which are a large part of the Cocos Ridge system. Once volcanoes, they are now ~2000m deep as a result of subsidence and wave action. As Jasmeet discussed, the Cocos and Nazca plates were spawned from the Farallon plate ~ 23 million years ago. It is thought that one cause for the weakening and subsequent split of the plates was the presence of a "hot spot" located near the present day Galapagos Islands. The now termed Galapagos hot spot has been upwelling mantle lava at a relatively constant rate resulting in the formation of sister ridges, the Cocos and the Carnegie. Although the ridges most likely began at the hot spot, The Cocos-Nazca spreading center divided them, sending the Cocos plate/ridge system on a NE vector to terminate at the Middle American trench, and the Nazca/Carnegie almost due East terminating at the Peru-Chile trench.

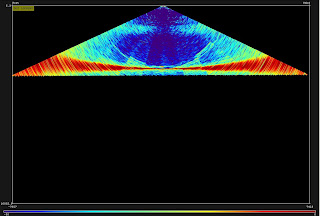

We also have been imaging the seabed with another sound propagating instrument named Echo-1. Echo-1 is a CHIRP (Compressed High Intensity Radar Pulse) sub-bottom profiler. Echo-1 emits a high frequency (3.5 kHz) sound, which can be best described as what else but.. a "chirp." It is largely responsible for the lack of sleep on this (and other) cruise(s). The resulting image (below) is that of the sedimentary layers to a varied depth, which is determined by the composition of the sediment/crustal materials reflectivity.

Hasta Luego, James

We also have been imaging the seabed with another sound propagating instrument named Echo-1. Echo-1 is a CHIRP (Compressed High Intensity Radar Pulse) sub-bottom profiler. Echo-1 emits a high frequency (3.5 kHz) sound, which can be best described as what else but.. a "chirp." It is largely responsible for the lack of sleep on this (and other) cruise(s). The resulting image (below) is that of the sedimentary layers to a varied depth, which is determined by the composition of the sediment/crustal materials reflectivity.

Hasta Luego, James

Day 11: Anomalies Abound

Something very exciting is happening....we are crossing the boundary between the Cocos and Nazca plates (see image below), which is a deep zone at the Panama transform fault, a very active active earthquake zone. This marks the end of our transit and the beginning of the marine geological survey that we set out to do. It all began with the Farallon plate, which underwent its final episode of plate fragmentation in the Miocene, when the Cocos plate split off and the remainder of the Farallon plate became the Nazca. The Cocos plate is spreading in a northeasterly direction, while the Nazca plate follows a easterly course; this spreading began at 23 Ma. A small portion of the northern rifted margin of the Farallon plate exists today, but is being subducted at about 50 km/m.y.

Beyond that, we were studying a map of magnetic anomalies earlier today, with ship tracks (and their magnetic records) from the 1950's to the present. On this cruise, we have a a magnetometer that trails 700 m behind the ship and records magnetic anomalies. This record is preserved in the crust at the time of formation and can be used to date it. We mostly view it in the context of a spreading axis, where parallel and symmetric (reflected) bands of known magnetic anomalies form, though they are often shifted and offset by plate movement thereafter. As we approach the equator, the local magnetics reverse, resulting in positive anomalies being recorded as negative. And as of late, the magnetic readings have been all over the place because of the Cocos Ridge....more on that later...

~Jasmeet

Beyond that, we were studying a map of magnetic anomalies earlier today, with ship tracks (and their magnetic records) from the 1950's to the present. On this cruise, we have a a magnetometer that trails 700 m behind the ship and records magnetic anomalies. This record is preserved in the crust at the time of formation and can be used to date it. We mostly view it in the context of a spreading axis, where parallel and symmetric (reflected) bands of known magnetic anomalies form, though they are often shifted and offset by plate movement thereafter. As we approach the equator, the local magnetics reverse, resulting in positive anomalies being recorded as negative. And as of late, the magnetic readings have been all over the place because of the Cocos Ridge....more on that later...

~Jasmeet

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Oceanopox

A more recent feature of our enthralling journey are these unusual, small-scale depressions on the ocean floor:

They're easy to miss, as they're typically no more than 100 meters deep...a small feature compared to many other structural features on the sea floor (fault scarps, seamounts, and even abyssal hills). In typical geological parlance, these are called "pock marks," and they record geologic events that are somewhat independent of their structural surroundings. Silicious (made of silica) tests, that is, the shells laid down by small or microscopic organisms (think clams or scallops, but silica instead of calcium carbonate, floating in the water column instead of rock or bottom-dwelling, and much, much smaller), fall to the sea floor after the organisms die. They form distinct layers of silicious material, typically containing an abundance of water incorporated into the chemical structure of the mineral.

Over time, as material newly deposited over the silicious layer begins to exert force on the silicious material, and, in some cases, as heat from surrounding structural activity (volcanism, dykes, et cetera) surrounds the silicious material, the water is squeezed or heated out of the chemical structure. As a result, the silica mineral greatly decreases in volume, and its mineral structure may also be changed. The result is not only a more widely recognizable mineral, opal, but also a depression in the Earth above the original material. As water is squeezed out and volume decreases, overlying material begins to sink down, creating these typically round pock marks. Their shape can vary, however, depending on how easily water can escape and via what conduits...for example, existing fracture and pore spaces (which occur especially in volcanic regions) can transport water away more effectively than other places around the silicious material, and therefore the resulting depression may show a shape bias towards those fractures and pore spaces. But even the strangest shapes are variants on the original circle -- crescents, ovals, and the like.

Over the next couple of days, we're all excited to start our intensive survey south of Panama and prepare data for analysis once it arrives back at Scripps.

Brad

They're easy to miss, as they're typically no more than 100 meters deep...a small feature compared to many other structural features on the sea floor (fault scarps, seamounts, and even abyssal hills). In typical geological parlance, these are called "pock marks," and they record geologic events that are somewhat independent of their structural surroundings. Silicious (made of silica) tests, that is, the shells laid down by small or microscopic organisms (think clams or scallops, but silica instead of calcium carbonate, floating in the water column instead of rock or bottom-dwelling, and much, much smaller), fall to the sea floor after the organisms die. They form distinct layers of silicious material, typically containing an abundance of water incorporated into the chemical structure of the mineral.

Over time, as material newly deposited over the silicious layer begins to exert force on the silicious material, and, in some cases, as heat from surrounding structural activity (volcanism, dykes, et cetera) surrounds the silicious material, the water is squeezed or heated out of the chemical structure. As a result, the silica mineral greatly decreases in volume, and its mineral structure may also be changed. The result is not only a more widely recognizable mineral, opal, but also a depression in the Earth above the original material. As water is squeezed out and volume decreases, overlying material begins to sink down, creating these typically round pock marks. Their shape can vary, however, depending on how easily water can escape and via what conduits...for example, existing fracture and pore spaces (which occur especially in volcanic regions) can transport water away more effectively than other places around the silicious material, and therefore the resulting depression may show a shape bias towards those fractures and pore spaces. But even the strangest shapes are variants on the original circle -- crescents, ovals, and the like.

Over the next couple of days, we're all excited to start our intensive survey south of Panama and prepare data for analysis once it arrives back at Scripps.

Brad

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Day 9: Are we there yet?

Well guys, nine whole days have gone by, and we have accomplished a lot as far as science and avoiding Hurricane Greg. The main events of today were the fire drill and a nice little trip to the mall. The drill included putting on our life vests for all of 10 seconds, only to put them back into our cabins and watch a 20 minute movie on boat safety. I wish we had done this the first day...perhaps it would've calmed my nerves about being on a ship for the first time! After the drill, the chief mate opened up the store locker, and sold us some R/V Melville T-shirts. Now, I have a souvenir to remember this trip forever.

We have four more days left until we reach port. Some of us are anxious to get to dry land that doesn't move 24/7...or maybe that could be just me.

As for science, today Ben (the lead technician) took a few of us on a tour of the lower lab. He showed us the gravimeter, which measures differences in the gravitational force among different places in the world. It's a very old piece of scientific equipment, dating back to the 1960s.Very old stuff.

I also got to launch an XBT today. Wahoo! On a more depressing note, today while launching my first XBT, I experienced a great loss. My old, weathered, Matisse hat decided to descend into the depths of this great ocean. I've had it for a whole year now, and it has endured a lot. I guess the ocean breeze was too much for it. Good bye, old friend.

Until next time!

Mackenzie

We have four more days left until we reach port. Some of us are anxious to get to dry land that doesn't move 24/7...or maybe that could be just me.

As for science, today Ben (the lead technician) took a few of us on a tour of the lower lab. He showed us the gravimeter, which measures differences in the gravitational force among different places in the world. It's a very old piece of scientific equipment, dating back to the 1960s.Very old stuff.

I also got to launch an XBT today. Wahoo! On a more depressing note, today while launching my first XBT, I experienced a great loss. My old, weathered, Matisse hat decided to descend into the depths of this great ocean. I've had it for a whole year now, and it has endured a lot. I guess the ocean breeze was too much for it. Good bye, old friend.

Until next time!

Mackenzie

Day 8: Fracture Zones

We've traversed abyssal hills, rise crests, and now fracture zones. They were first discovered by Bill Menard (of Scripps) in the 50's off the coast of Mendocino, California. It created quite a stir in the scientific world at the time, given that nothing analogous had been discovered on land, and these features were quite frequent along the ocean floor. It is a distinctive feature in undeformed crust, and they appear in parallel bands. In the image below, it is the deep (coded blue) area in the lower right part of the swath.

In the image above, of a side scan, it shows reflectivity of the sonar. Therefore, more dense regions such as rocks appear darker as they reflect more sound. Less dense regions of the ocean floor such as sediment appear lighter, as they reflect less

Speaking of color-coded bands, I fear that if I ever go in a submersible to the ocean floor, I will expect a world of rainbow color. But I have to remind myself that these colors are just our way of coding the information. And as pretty as they are, seeing the sea floor in person would be wondrous in its own right.

In other news, our knowledge of the ship and nautical world continues to grow. We had a tour to the engine room a couple of days ago, looked out of underwater portholes at the great blue, and will continue our explorations with a nautical astronomy class this evening. We have a few photos floating around--will try to them posted sooner than later...

Fair Winds,

~Jasmeet

In the image above, of a side scan, it shows reflectivity of the sonar. Therefore, more dense regions such as rocks appear darker as they reflect more sound. Less dense regions of the ocean floor such as sediment appear lighter, as they reflect less

Speaking of color-coded bands, I fear that if I ever go in a submersible to the ocean floor, I will expect a world of rainbow color. But I have to remind myself that these colors are just our way of coding the information. And as pretty as they are, seeing the sea floor in person would be wondrous in its own right.

In other news, our knowledge of the ship and nautical world continues to grow. We had a tour to the engine room a couple of days ago, looked out of underwater portholes at the great blue, and will continue our explorations with a nautical astronomy class this evening. We have a few photos floating around--will try to them posted sooner than later...

Fair Winds,

~Jasmeet

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Calm after the Storm

Last night, roughly 100 miles southwest of Acapulco, we experienced what was soon to be tropical storm Greg. Starting with light wind, swell and occasional rain squalls, conditions rapidly evolved into an increasingly agitated ocean with observed gusts as high as 55 knots and seas up to 4 meters. The Melville trudged on into the wind and waves with the occasional thud as the bow dug into the sea, while inside, most were asleep with the exception of those on watch or a few too interested to stay in their cabins. Word has it there were some spectacular views from the bridge of waves crashing over the bow. As the sun rose this morning we were greeted by calming seas, sunny skies and light wind on our last leg in Mexican waters.

Brian Franz

Brian Franz

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Stormy Seas

The ship is really rockin' tonight. There is a storm which is driving ~40 knot winds ~40 degrees off of the bow. Peter did a quick (although suspect) calculation and determined that as a result of the storm we will not lose much time. Time is very important as if all goes well we will have roughly 48 hours in the survey area south of Panama. Speaking of time I thought it would be a perfect time to follow up Mackenzies story of the ping edits with a view of swath sonar data that due to the storm will need to be edited. The roll (side to side), pitch (front to back), and yaw (up and down) actions of the ship cause the multibeam to miss pings as they return which causes "noise" in the data. Aside from that all is well.

Till next time, James

Till next time, James

Monday, August 15, 2011

Day Six: The Witching Hour

It is the night shift here on the Melville, and once again I find myself in the main lab with a very tired Dr. Lonsdale and Jasmeet. But I think we all are finally used to our abnormal sleeping schedules. Currently, we are chugging along a nice fault scarp next to a huge deep ocean trench, which should yield some interesting bathymetry. I am definitely learning a lot, and increasing my intellectual worth.

Aside from monitoring the CHIRP, multibeam, and magnetometer, we also finished up editing what are called "ping files". When you drive over the sea floor, the multibeam creates a swath, and each ping the beam sends out is logged as data into a file. The beam, however, picks up a lot of extra fuzz on the sides, which can give inaccurate bathymetry. Our job then becomes to edit each file, and make sure the swath looks okay, so that it gives accurate data once it's on the map.

As far as wildlife goes, I still have yet to see any dolphins or whales. I seem to sleep through all the really good stuff. However, I did see two sea turtles, and the flying fish never cease to amaze me. Everyone on the crew is becoming more gregarious around me, and the cook even gave me a few smiles yesterday. I think it's because I eat a lot of his food, which is ridiculously good. If you do not like his food, you are most definitely not human. I worked out on the bike below decks just now before the midnight shift, which produced a weird feeling of boat-rocking vertigo as well as the usual sweaty uncomfortable feeling that comes with working out. Fun.

Science calls, so until next time!

Mackenzie

Aside from monitoring the CHIRP, multibeam, and magnetometer, we also finished up editing what are called "ping files". When you drive over the sea floor, the multibeam creates a swath, and each ping the beam sends out is logged as data into a file. The beam, however, picks up a lot of extra fuzz on the sides, which can give inaccurate bathymetry. Our job then becomes to edit each file, and make sure the swath looks okay, so that it gives accurate data once it's on the map.

As far as wildlife goes, I still have yet to see any dolphins or whales. I seem to sleep through all the really good stuff. However, I did see two sea turtles, and the flying fish never cease to amaze me. Everyone on the crew is becoming more gregarious around me, and the cook even gave me a few smiles yesterday. I think it's because I eat a lot of his food, which is ridiculously good. If you do not like his food, you are most definitely not human. I worked out on the bike below decks just now before the midnight shift, which produced a weird feeling of boat-rocking vertigo as well as the usual sweaty uncomfortable feeling that comes with working out. Fun.

Science calls, so until next time!

Mackenzie

Day 4 (on Day 5): the East Pacific Rise

What you're looking at is a shaded three-dimensional perspective of a section of the East Pacific Rise (EPR), where new oceanic crust is actively being produced, and the distinction between the Pacific and Cocos plate is set (for our journey at least). The freshly exhumed rock, from the mantle, is very hot; but, eventually it cools to a point where it records the magnetic field around it (look up the Curie temperature). Using this information, we are able to tell a story about the history of the crust over a very broad scale (hundreds of kilometers in some cases!), which is why I mentioned the San Andreas fault a few days ago. Soon enough we'll be using this kind of information to describe the history of the crust (microplate interaction, faulting, etc.) in the vicinity of Panama, so stay tuned.

On a more important note: I just realized (reading my title) that I may have a future in geo-poetry. Well, probably not, but at least I just made up the term for it - I think I'll start a Wikipedia page...

-Andy

On a more important note: I just realized (reading my title) that I may have a future in geo-poetry. Well, probably not, but at least I just made up the term for it - I think I'll start a Wikipedia page...

-Andy

Day 5 and Sounding!

It's very interesting being at sea. I find that when I am not working I have a lot of time for contemplation. This is important for someone like myself who's about to enter his senior year as to what it is that I truly want to do? I find Marine Geology by way of sound fascinating, and this cruise (aside from the fact that I have been writing/fine tuning script for the last 4 days) only affirms that this is what I would like to make my lifes work. Now for some science! Below are images created by the EM-122 multi-beam sonar. The first is a 3D rendition of the latest pings as we progress south to Panama. The second is a side view of the sonar propagation through different levels of the water column. Lastly I have a screen shot of the SVP (Sound Velocity Profile) of our latest XBT. To plot it the temperature is measured as a function of time to a depth of 1000 meters. A salinity profile is then applied to the curve and from it we get sound speed through the water column. This is not an exact measurement, however, we do our best to be careful in it's deployment as a small difference when integrated over the depth may lead to large errors. As I said in the ship tracker we crossed the East pacific Rise yesterday evening and my shipmate Andy can't wait to talk about it. So enjoy the screen shots and bye for now.

~James

~James

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Day Three: Bowditch, On Watch

We're all adjusting to our watch schedules, 4 hours at a time, every twelve hours. Beyond the array of computer screens that we monitor, we have a new assignment: reading chapters from the Bowditch manual on navigation--in preparation for our celestial navigation class to come (compliments of the Chief Mate) and the possibility (hopefully never realized) of navigating lifeboats and/or passing through a tropical cyclone. It's definitely great to learn more about all things nautical; we are apparently to be tested--theoretical or practical, TBD.

Last night's watch was rather exciting, as we decided to launch an XBT (Expendable Bathythermograph), in order to determine the thermocline (change in temperature with depth) of the surrounding waters. It starts off with anticipation--there's a cartridge loaded onto a XBT-gun. Novices are warned of the recoil and the sound. When launched, however, it falls gently into the ocean, with little flare. As it falls at 6 knots, the XBT provides a profile of the temperature, which is key in determining the speed of sound, which then informs the seafloor depth given by Multibeam and CHIRP.

Speaking of watches, some of us helped sight and photograph a rare bird, identified by our resident bird-watching expert. It is a Socoro Mockingbird, likely blown off its little island by a hurricane, and finding refuge on the Melville Deck. We do hope he sights land, and finds his way there.

--Jasmeet

Last night's watch was rather exciting, as we decided to launch an XBT (Expendable Bathythermograph), in order to determine the thermocline (change in temperature with depth) of the surrounding waters. It starts off with anticipation--there's a cartridge loaded onto a XBT-gun. Novices are warned of the recoil and the sound. When launched, however, it falls gently into the ocean, with little flare. As it falls at 6 knots, the XBT provides a profile of the temperature, which is key in determining the speed of sound, which then informs the seafloor depth given by Multibeam and CHIRP.

Speaking of watches, some of us helped sight and photograph a rare bird, identified by our resident bird-watching expert. It is a Socoro Mockingbird, likely blown off its little island by a hurricane, and finding refuge on the Melville Deck. We do hope he sights land, and finds his way there.

--Jasmeet

Friday, August 12, 2011

Day two, part two.

As Brad mentioned previously, things are settling in a bit in many ways (mostly in our work/eat/sleep routine), but we're also coming upon some interesting geomorphology: Inactive spreading ridges. At the moment, we're transiting between the Rosanna and Rosa ridges - two in a system of seven en-echelon ridge/transform zones off the coast of Baja California Sur. We are, as I write, recording the magnetic field associated with the oceanic crust, which, when combined with precise laboratory dating of rock specimens, tells us about the history of such ridges. Previous studies have found that these ridges were active producing new oceanic crust from approximately 12 to 6 million years ago, and are interpreted as excellent evidence of microplate capture, a theory which helps explain, for example, the development of the San Andreas fault hundreds of kilometers away.

Andy

Andy

Technically challenging, (un)turbulent, titillating day TWO

This morning, a baffling rumor began circulating: it seems that, after a day, we are in fact a day behind. Besides the mathematical questions such a conclusion might raise, even more profoundly inexplicable is the fact that the situation seems remarkably mundane. We're a day behind, and we still keep the same watches and follow the same protocols. I wonder, given our track record, whether by our twelfth and final day we will be twelve days behind? Perhaps, though, our already spectacular weather conditions will improve, our efficiency will increase more than tenfold, and we will arrive only two days late. It is, I think, a valid question, but only in the same baffling context from which the rumor was born.

Of course, I speak (primarily) in jest, although our fantastic weather, friendly crew, excellent food have not been uninterrupted by technical issues. The last 24 hours (indeed, nearly two-thirds) of our multibeam bathymetry data have been compromised by a false stairstepping effect introduced as a relic of the equipment's transmission sectors. Think of an equilateral triangle, point up, which is divided into eight equal sections with dividers converging at the upper point. Each division represents a transmission sector, and each is transmitted from a single source on the boat (represented by that upper point). Our problem occurs at the divisions of each of these sectors...the leftmost edge of one sector, for example, returns a depth that is offset by a constant value from the rightmost edge of the sector to the left of the first (close your eyes and visualize). The problem is less of an issue here, where our data are merely an addition to the relative plethora of bathymetric data in this area compared to our destination south of Panama.

We've all largely adjusted to life on the ship: meal times have become more intuitive, more of the ship has been explored (a tour of the engine room is supposedly in the works), and we are beginning to work our watches more independently. So far, life is interesting and exhausting...however I reserve final judgement for the flight attendants on my way home, who will almost certainly not re-transmit my almost certain oncoming contempt for not only oceanography, but science in general. Okay, okay, not true: I find bathymetry and magnetic anomalies perhaps awkwardly enthralling.

Brad Peters

Of course, I speak (primarily) in jest, although our fantastic weather, friendly crew, excellent food have not been uninterrupted by technical issues. The last 24 hours (indeed, nearly two-thirds) of our multibeam bathymetry data have been compromised by a false stairstepping effect introduced as a relic of the equipment's transmission sectors. Think of an equilateral triangle, point up, which is divided into eight equal sections with dividers converging at the upper point. Each division represents a transmission sector, and each is transmitted from a single source on the boat (represented by that upper point). Our problem occurs at the divisions of each of these sectors...the leftmost edge of one sector, for example, returns a depth that is offset by a constant value from the rightmost edge of the sector to the left of the first (close your eyes and visualize). The problem is less of an issue here, where our data are merely an addition to the relative plethora of bathymetric data in this area compared to our destination south of Panama.

We've all largely adjusted to life on the ship: meal times have become more intuitive, more of the ship has been explored (a tour of the engine room is supposedly in the works), and we are beginning to work our watches more independently. So far, life is interesting and exhausting...however I reserve final judgement for the flight attendants on my way home, who will almost certainly not re-transmit my almost certain oncoming contempt for not only oceanography, but science in general. Okay, okay, not true: I find bathymetry and magnetic anomalies perhaps awkwardly enthralling.

Brad Peters

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Day One.

August 11, 2011

Many of the students slept on board last night, and mustered at 6:30 for passport collection, breakfast, and safety training. After the ship's horn sounded in our ears, we knew we were on our way. It didn't take long for the ship to begin pitching, rolling, and heaving (ship terms... no big deal), but fortunately the seas are remaining calm. Our course is constantly changing (a few degrees here or there) as Dr. Lonsdale decides what is, and perhaps more importantly, what could be worth exploring; we've made great progress on a journey to Panama.

Here's a reduced sample of some of the data we're collecting: High resolution seafloor soundings along our course.

Many of the students slept on board last night, and mustered at 6:30 for passport collection, breakfast, and safety training. After the ship's horn sounded in our ears, we knew we were on our way. It didn't take long for the ship to begin pitching, rolling, and heaving (ship terms... no big deal), but fortunately the seas are remaining calm. Our course is constantly changing (a few degrees here or there) as Dr. Lonsdale decides what is, and perhaps more importantly, what could be worth exploring; we've made great progress on a journey to Panama.

Here's a reduced sample of some of the data we're collecting: High resolution seafloor soundings along our course.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)